The audacious early days of CIO magazine

In his new book, "Future Forward: Leadership Lessons from Patrick McGovern, the Visionary Who Circled the Globe and Built a Technology Media Empire," author Glenn Rifkin tells the story of the International Data Corp. (IDC) and International Data Group (IDG) founder.

Let’s try it

As often happened, McGovern was a good decade ahead of his peers and competitors when it came to fostering innovation within IDG. The concept of “intrapreneurship” gained wide popularity in the 1980s as innovation became the watchword for late twentieth century corporate success. Leaders such as Steve Jobs, Richard Branson, and later Larry Page and Sergey Brin were vocal proponents of “Let’s try it.” The payoffs were world-changing. The list of breakthrough products and services spawned by internal innovation efforts is impressive. Among them:

Apple’s iPhone, iTunes, iPod, and iCloud

Google’s Gmail

Sony’s PlayStation

3M’s Post- it Notes

Virgin Air and Virgin Galactic

McGovern foresaw the power of such thinking from the earliest days of IDG. His decision in 1978 to get off a plane in Beijing without a visa to visit a country that had yet to establish diplomatic ties with the United States was a classic “Let’s try it” moment that eventually spawned a highly lucrative result. His business sensibility mirrored his personality. He was driven, tireless, and highly competitive, but he had no craving for the spotlight or the lion’s share of the credit. He made sure senior leaders within IDG were publicly feted and rewarded for out-of-the-box thinking that drove growth. Worldwide managers meetings were inspiring gatherings during which top performers were lauded by their peers and given cash rewards. By encouraging and supporting this kind of entrepreneurial spirit within IDG, the company reaped massive benefits.

For example, after 15 years working for IDC, most of that time as vice president of marketing, Joe Levy believed that the money and the fun were on the publishing side of the business. IDC, the company’s research arm, had struggled unsuccessfully toward profitability for much of that time. But Levy had soldiered on until 1986 when IDC hired Carl Masi as its new CEO. Masi came from Wang Laboratories, at the time a noted minicomputer maker, and he had some big ideas about how to improve IDC’s lagging fortunes. At an early 1987 executive committee meeting, Masi presented a grandiose plan to McGovern that involved spending a lot of money and making significant investments. Several IDC managers presented similarly optimistic plans, and then Levy, as VP of marketing, spoke last. He had one foil for the overhead projector: a picture of the sinking of the Titanic. “I looked at Pat, and I’m not a particularly brave person, but I said, ‘Pat, we don’t stand a chance in hell,’” Levy said. “Needless to say, that didn’t ingratiate me with Carl Masi, who was my new boss.” “Why not have a chief information officer, a CIO?” And beyond that, why not create a magazine for and about CIOs “and make them famous for their use of technology instead of just writing about the technology itself?”

Indeed, after the meeting, Masi took Levy into his office and told him he’d be gone in six months, so he ought to start looking for a new job. Levy did just that. But instead of looking outside the company, he thought about McGovern’s edict: Let’s try it. And he came up with an idea that had been percolating in his head. IDC had been publishing countless reports about the heads of data processing as they were becoming more and more crucial to the business side of their firms. Despite their growing importance, these techies rarely received the respect and acknowledgment from corporate executives. They were considered integral parts of the back office but not savvy business leaders. Levy thought about all the C- level titles, from CEO to CFO, and thought, “Why not have a chief information officer, a CIO?” And beyond that, why not create a magazine for and about CIOs “and make them famous for their use of technology instead of just writing about the technology itself?” Levy thought.

He sent a note to McGovern with his idea, and not surprisingly, McGovern responded by saying “Give me a business plan.” Levy knew little about business plans, but he put something together quickly and sent it along. His actual goal, he recalled, was simply to outlast Carl Masi, a fellow whom he assumed would flame out quickly in IDG’s unique environment, and then Levy could return to his day job running marketing at IDC. Levy figured he could spend at least several months researching the concept, mostly by visiting these CIOs and polling them to see if there was an audience for the prospective publication. He quickly realized he had tapped into something serious.

“I would be talking to people, and they would ask when the first issue was coming out,” Levy recalled. “So I would make up a date. But as time went on, they’d ask me for a rate card.”

Levy, in his marketing capacity at IDC, had coordinated magazine supplements based on IDC research for Fortune magazine. He helped the Fortune salespeople sell advertising and learned about Fortune’s advertising rates. The supplements had been extremely profitable for Fortune and were moneymakers for IDC, so when asked about his new magazine, he quoted just below Fortune’s rate card. I figured this was a nice buildup of frequent flyer miles, but what I didn’t realize was that to a lot of these advertisers, it sounded like a great idea.

Nonetheless, he was quoting close to the highest cost per thousand readers (CPM) rate in the magazine world. At the time, he never envisioned an actual magazine being born. This whole effort was a stalling tactic. But as Levy played it out, he got a faint inkling that his stalling tactic was morphing quickly into an actual publication. Levy came up with an initial circulation figure of 25,000, and as the fictional ad deadline for the first issue approached, he began to get panicky. “I figured this was a nice buildup of frequent flyer miles, but what I didn’t realize was that to a lot of these advertisers, it sounded like a great idea,” he said. “We started getting insertion orders for ads, and I finally had to tell Pat, ‘We’ve got a big problem.’ Pat said, ‘What problem?’ and I said, ‘We have insertion orders for a magazine that doesn’t exist.’ And he said, ‘It does now!’”

Thus CIO magazine was born, albeit without any editorial, sales, or production staff. Suddenly thrust into an editorial role, Levy fought off panic. He thought he might approach Computerworld, IDG’s highly successful flagship publication, and make CIOa supplement to the weekly newspaper. But McGovern nixed the idea.

Years later, he confided to Levy that he was convinced that an association with Computerworld would have caused CIO to fail. Computerworld, McGovern reasoned, would have insisted on doing everything by the book, and that was exactly what Levy was avoiding. His plan and his advertising rates were audacious, and McGovern believed that audacity was what fueled CIO’s success.

CIO debuted in 1987 and was profitable from the start. Levy began with low overhead: just four employees, including himself and a coterie of freelancers. Once the magazine got traction, he initiated a series of executive conferences for CIOs in order for advertisers to mingle with top technology executives. Seemingly everything Levy did turned to gold. CIO found an instant and appreciative audience right out of the gate. Being on a CIO cover, which bore a slight resemblance to TIME magazine, became a badge of honor. Due to the magazine’s cachet, exhibitors paid a steep price—up to $50,000—to attend the conference and were also required to pay $250,000 in advertising dollars for a 12- month period. At its height under Levy, CIO became an $80 million business unit of IDG. McGovern was pleased. “As long as I made my numbers, I would never see him or hear from him,” Levy said. “He’d send me ideas from time to time, but I ran it as if it was my own company.”

Local author pens book on tech CEO who led with ‘kindness’

Glenn Rifkin is an author and former columnist at the Concord Journal. Now living in Acton, Rifkin published his latest book, “Future Forward,” in September. Ahead of Rifkin’s Oct. 21 author talk at the Concord Bookshop, he shared some of the information he learned writing “Future Forward” and its subject, Patrick McGovern.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length. What is “Future Forward” about?

“Future Forward” is a look at the life and leadership lessons of Patrick McGovern, the founder and CEO of International Data Group. IDG, under McGovern’s guidance for nearly 50 years, grew into a global technology media empire with 300 publications in nearly 100 countries with 280 million readers.

Among IDG’s most notable publications are Computerworld, Infoworld, PCWorld, Macworld and CIO magazine. IDG also became a major venture capital firm under McGovern and now has venture capital arms in China, Vietnam, India and South Korea. McGovern was a unique leader whose principles-based ideas about how to run a company made IDG a remarkable, familial kind of company. The book offers 10 of these lessons for business readers and prospective entrepreneurs.

What about Patrick McGovern made you want to write about him?

I worked at IDG as a writer and editor at Computerworld in the 1980s and I got to meet and know Pat quite well. I was amazed and impressed how much his employees meant to him and how generous he was as a CEO, especially in an era known for “Greed is Good.”

For example, as the holidays approached in December, he would visit every IDG office in the U.S. and go cubicle-to-cubicle meeting every employee, from editors to production workers, and greet them by name, chat about their work, their families, their concerns and then hand each one a holiday card stuffed with a generous Christmas bonus. When I was there, there were at least 5,000 employees in the U.S., so it was a gargantuan task. But he insisted on doing it every year.

After Pat died in 2014, his son Patrick III decided he wanted a book written about his father. Several people gave him my name and he called. The rest is history.

How was the process of writing “Future Forward” different from your previous books?

The writing process wasn’t different. I do a ton of research, interview a legion of people and then jump into the arduous task of writing, editing and rewriting. But this project was a labor of love and an especially joyous undertaking, mostly due to the kinship I formed with Patrick III during the process. We traveled to China and India together, places where McGovern had established successful IDG entities, and he was a sounding board for the book from start to finish.

Also, having worked at the company, I got a chance to reconnect with a lot of former colleagues who shared their stories and insights about Pat. The whole thing felt more like a reunion than a book project.

What was the most surprising thing you learned while doing research for the book?

I couldn’t find a single person to say something negative about Pat. The level of love and devotion to the guy, even to this day, is remarkable.

What lessons can aspiring entrepreneurs and business owners learn from this book?

The whole book is filled with lessons for aspiring business leaders, so I couldn’t list them all here. But if I had to offer one, it would be this -- doing well by doing good is not only possible, it is a totally winning strategy. Pat practiced leadership through kindness, empathy, compassion, along with a firm and determined business vision. He was nobody’s pushover, but he proved that nice guys can and do finish first sometimes.

The story of tech pioneer & IDG founder Pat Mcgovern

IDG is the world’s largest technology media company. They help their global audience make the smartest technology purchasing decisions. Like many of you reading this, I grew up with Windows For Dummies Books, SQL for dummies and any tech subject was covered by those books that were all made by IDG.

Essentially many of these IDG books transformed how the global community grew to understand the enormous potential of computers and started to think about how they would change the world. Founder Pat McGovern was a pioneer in the information technology industry, in his own way, he was equally as vital as Steve Jobs or Bill Gates. But he never sought the spotlight and many of this contributions have been overlooked.

Pat McGovern, was the man who turned IDG into a $3 billion technology media and venture capital empire and eternal optimist that put people and making a difference first and kept himself in the shadows. Glenn Rifkin worked with Pat McGovern and has written a book called Future Forward where he shares McGovern’s legacy so provides leadership lessons so that others can learn from this inspiring man.

On today’s daily tech podcast, you will learn how one innovative leader transformed an entire industry into a global media empire and learn more about the visionary founder and chairman of IDG. A warm and genuinely inspiring story of how tech and media have evolved since 1964. As a host, I loved learning about how one innovative leader saw an industry need and built a leading global business on the foundation of quality.

A great example of what can be achieved with passion, innovation, and a “let’s try it” attitude. I genuinely hope that Pat McGovern’s legacy will live on in every person that listens to this episode.

How the founder of IDG and IDC created an empire (German)

Patrick McGovern, Gründer von IDC und IDG - und damit auch von der COMPUTERWOCHE und CIO-Magazin - starb 2014 im Alter von 76 Jahren. Der US-Journalist Glenn Rifkin hat ein Buch geschrieben, das das Leben des Medienmoguls unterhaltsam nachzeichnet und eine Menge darüber verrät, was Unternehmer mitbringen müssen, um erfolgreich zu sein.

Große Unternehmer und Gründerpersönlichkeiten haben oft ganz besondere Eigenschaften und nicht immer sind diese sympathisch. Ellbogenmentalität und Härte gehören dazu, manchmal auch Narzissmus und Größenwahn. Pat McGovern war anders, und es ist kein Zufall, wenn sich Ethernet-Erfinder Bob Metcalfe in der Biographie "Future Forward" mit folgenden Worten zitieren lässt: "McGovern hat damals sein Startup nicht groß gemacht, indem er erfahrene und energiegeladene Menschen eingestellt hat. Er hat Entrepreneure eingestellt, und er hat Ineffizienz toleriert, weil ihm die Energie dieser Entrepreneure wichtiger war."

Neugier und Risikobereitschaft, aber auch der Mut, Grenzen und Konventionen zu überwinden, waren hervorstechende Charaktereigenschaften von McGovern, der es damit zu einem der weltweit größten Verleger, Unternehmer und Investoren brachte. Salesforce-Gründer Marc Benioff traf McGovern 1999, im Gründungsjahr der Kalifornier, am Flughafen von San Francisco. Der Startup-Gründer hatte damals am Gate nur ein paar Minuten Zeit, und er wusste, dass McGovern, der längst Herrscher über ein Medienimperium war, auch in hoffnungsvolle Startups investierte.

Im Vorwort der Biographie schreibt Benioff: "Ich erzählte ihm, was ich vorhatte, dass ich den Kauf von Software so einfach wie eine Buchbestellung bei Amazon machen wollte. Als er mich angehört hatte, bot er mir direkt an zu investieren. Anders als ein Dutzend von Investoren im Silicon Valley, bei denen ich es zuvor versucht hatte, erkannte McGovern sofort, dass es im ITK-Markt eine seismische Verschiebung in Richtung Cloud Computing geben würde." McGovern wurde zu einem der ersten Salesforce-Investoren, und die Familie erzählte Benioff nach dem Tod des IDG-Gründers, dass er sich von seinen Anteilen nie getrennt habe. "Damit hat er mindestens einen 1000-Prozent-Gewinn gemacht", stellt Benioff fest.

Anderen zuhören, Märkte verstehen, Risiken eingehen, dabei aber authentisch bleiben und nicht die eigene Linie verlassen - das waren laut Biograph Rifkin wichtige Charaktereigenschaften von McGovern. So baute er das Medienimperium IDG auf, das Marktforschungsunternehmen IDC und auch die Investmentgesellschaft IDG Ventures, die nicht nur in den USA, sondern auch in Vietnam, India, Korea und vor allem in China zu einem frühen Zeitpunkt Milliardensummen investierte.

In seinen Geschäftsentscheidungen scheute sich McGovern nicht, ungewöhnliche Pfade zu betreten. York von Heimburg, President International bei IDG Communications und seit 1992 im Unternehmen, gibt im Buch ein Beispiel: "In den US-Unternehmen der 1960-er Jahre lag der Fokus auf Wachstum. Größe war alles. Dabei herrschte Konsens darüber, dass die Betriebe zentral aus den USA heraus gelenkt werden müssten. Pat tat genau das Gegenteil. In dieser Zeit ein dezentral strukturiertes Unternehmen aufzubauen, in dem Glauben, dass Business, Informationsflüsse und Kundenbeziehungen lokal besser funktionieren - das war absolut revolutionär."

Heute Deutschland, morgen China, übermorgen der Rest der Welt

In Deutschland startete McGovern 1974 mit der COMPUTERWOCHE, dem deutschen Pendant zur 1967 gegründeten "Computerworld". Der IDG-Gründer hatte erkannt, dass Deutschland Europas größter Markt für elektronische Datenverarbeitung war und wollte von hier aus in Europa expandieren. Dabei stellte die politisch prekäre Situation in einem Europa, das durch den Eisernen Vorhang gespalten war, für ihn kein Hindernis dar - im Gegenteil. McGovern und der spätere COMPUTERWOCHE-Verleger und -Geschäftsführer Eckhard Utpadel machten es zu ihrem erklärten Ziel, Information auch zu den Menschen zu bringen, die politisch abgeschnitten waren.

Mit diesem Pioniergeist veröffentlichte McGovern als erstes westliches Verlagshaus eine Publikation im damals noch tief maoistisch geprägten China. Für York von Heimburg stellt diese Entscheidung einen wichtigen Schritt in der IDG-Geschichte dar. McGovern war der erste in der Volksrepublik tätige ausländische Verleger, und er gründete auch das erste amerikanisch-chinesische Joint Venture. Heute ist der bereits 1992 aufgelegte Venture Fund "IDG Capital" mit seinen 700 Beteiligungen und über 160 erfolgreichen Exits der größte internationale Venture Fund in China und der achtgrößte Fund weltweit. Auch bei populären chinesischen Internet-Firmen wie Baidu und Tencent war IDG von Anfang an beteiligt.

McGovern hatte erkannt, auf welcher Grundlage westliche Unternehmen in China Erfolg haben können: Im Reich der Mitte sind gute persönliche Beziehungen das Fundament für geschäftlichen Erfolg. Dementsprechend unternahm er mehr als 130 Reisen nach Fernost, lernte die Kultur kennen und behandelte die Belegschaft dort mit demselben Respekt, den er allen Mitarbeitern entgegenbrachte. McGovern hatte bald den Status eines Ehrenbürgers und erhielt Auszeichnungen, die kein anderer Abendländer davor je erhalten hat.

Eine Geschichte, die erzählt werden muss

Rifkins Buch erzählt die Geschichte einer Führungspersönlichkeit "die keine Grenzen kannte", wie es Axel Leblois, ehemaliger CEO von IDG, formuliert. "Jede Kultur lehrte ihn wertvolle Dinge, die er in seinen Führungsstil einfließen ließ. Er respektierte alle Menschen, unabhängig von ihrem Job-Titel oder ihrer Herkunft und das machte seine Menschlichkeit sehr greifbar für mich," fasst der Autor eine zentrale Erkenntnis aus seinen Recherchen zusammen.

Die verschiedenen "Lektionen" des Buches beleuchten diesen erfolgreichen Management- und Führungsstil in allen Facetten. Angefangen bei der Vision über Verhaltensweisen, Unternehmensstruktur und Management-Auswahl bis hin zum Umgang mit den Mitarbeitern. Natürlich bleiben auch die philanthropischen Leistungen McGoverns nicht unerwähnt: Rund 350 Millionen Dollar investierten er und seine deutsche Ehefrau Lore in ein Institut für Gehirnforschung am Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Boston - unweit vom IDG-Firmensitz in Framingham.

"Er wollte verstehen, wie das Gehirn funktioniert und er wollte neue Wege entdecken, Krankheiten zu vermeiden oder zu behandeln", schreibt Benioff. Deshalb habe er nicht nur Geld gespendet, sondern auch mit den Wissenschaftlern diskutiert, Touren durch das Institut organisiert und Leute wie ihn, Marc Benioff, als Unterstützer gewonnen.

Biograph Rifkin schreibt seit fast 30 Jahren für die New York Times und verfasste Beiträge für zahlreiche weitere Publikationen, darunter das Wall Street Journal und die Harvard Business Review. In den 1980-er Jahren arbeitete er als leitender Redakteur bei der Computerworld und lernte den Führungsstil von Pat McGovern aus erster Hand kennen. Der Kontakt riss in den Folgejahren nie ab. Nach seinem Weggang von IDG führte Rifkin zahlreiche Interviews mit McGovern, in denen die Idee für das Buch entstand. (rs)

Computerworld Czech Republic. Future Forward: Leadership skills lessons from Patrick McGovern's IDG founder (Czech)

Před více než 50 lety, na úsvitu počítačového věku, založil Patrick J. McGovern společnost International Data Corp., a později i International Data Group, mateřskou firmu PCWorldu, která vznikla v roce 1967.

Z těchto skromných začátků dokázal McGovern, jenž zemřel v roce 2014, postupně vytvořit globální vydavatelské a datové impérium. Toto impérium se nakonec rozrostlo na zhruba 300 různých publikací v 97 zemích světa, 460 webů a 700 akcí zaměřených na všechny aspekty odvětví IT. A v roce 2000 umožnilo McGovernovi spolupracovat s MIT na tvorbě McGovern Institute for Brain Research (McGovernova institutu pro výzkum mozku).

Ve své nové knize s názvem „Future Forward: Leadership Lessons from Patrick McGovern, the Visionary Who Circled the Globe and Built a Technology Media Empire“ (Kupředu do budoucnosti: Lekce vůdčích schopností od Patricka Mc Governa, vizionáře, který obkroužil svět a vybudoval technologické mediální impérium) dokumentuje její autor Glenn Rifkin McGovernův příběh, jakož i lekce vůdčích schopností, které získal v průběhu psaní.

V knize se píše například o tom, jakým způsobem McGoverna v roce 1964 napadlo založit IDC a jak to vedlo ke zrození Computerworldu. V té době pracoval jako redaktor magazínu Computers and Automation se sídlem v Newtonu ve státě Massachusetts, a rychle vstřebával novinky z rodícího se odvětví IT… Následuje výtah z knihy, kde se popisují právě okolnosti vzniku Computerworldu:

„(…) Pro odpovědi na tyto otázky neexistoval žádný spolehlivý zdroj. Ve skutečnosti existovala pouze jediná publikace, měsíčník zvaný Datamation, který začal v roce 1957, v době, kdy korporátní počítačový průmysl v plenkách. McGovern si představoval něco mnohem dynamičtějšího a bezprostřednějšího. Computerworld měl být týdeníkem, jehož účelem bylo pokrývat rychle se měnící odvětví skupinou redaktorů a reportérů, kteří by pokryli trh a psali kvalitní články o výrobcích i koncových uživatelích. Jako jakékoliv jiné důvěryhodné noviny psal i Computerworld kromě dobrých zpráv i o těch špatných, a rané palcové titulky jako ‚Pád pevného disku, v bance zničeno tisíc záznamů‘ nebo ‚Datový systém nemocnice přišel o všechna data‘ odvětvím, jež na takovou upřímnost a dobré načasování informací nebylo zvyklé, pořádně zatřásly.

Na rozdíl od Datamation a dalších časopisů řízených reklamou, které se v oboru začínaly objevovat, prodával Computerworld společně s reklamami i placené předplatné. V prostředí, v němž byla všechna obchodní periodika postavena na „regulovaném nákladu“ nebo neplaceném předplatném, se McGovern rozhodl využít recept Lou Radera: jestliže zajistíte, aby nějaký produkt působil hodnotně, získá okamžitou věrohodnost a lidé za něj budou platit. Zavedením poplatku za předplatné se Computerworld nejenže dostal rychle do zisku, ale získal prestiž a věrohodnost, díky které se rychle stal biblí odvětví informačních technologií. Computerworld – se svými celými 12 stránkami – debutoval v červnu 1967 na jednom počítačovém veletrhu v Bostonu. Do dvou týdnů měl McGovern na palubě 20 tisíc platících předplatitelů. Periodikum začalo neprodleně růst tak, jak se mu nezdálo ani v těch nejdivočejších snech. Jeho vášeň pro sdělování informací, jež by mohly měnit životy lidí, nalezla svůj základní stavební kámen.

Computerworld znamenal počátek zběsilého období růstu a expanze, který dal vzniknout dlouhému seznamu vůdčích výzev, jež McGovern v následujících pěti dekádách zkrotil. V odvětví, které se hemžilo brilantními mladými mozky a tsunami nových myšlenek, jež měly změnit svět, znamenaly kvalitní vůdcovské schopnosti, tato výjimečná, ale nepostradatelná přísada, klíčový rozdíl mezi vítězi a poraženými.“

Glenn Rifkin On The Legacy Of IDG Founder Patrick McGovern

One of the most influential media empires in the world can be traced back to the late Patrick McGovern, an MIT graduate working out of a house in Newton.

He would develop the tech media company International Data Group — IDG — in 1964.

IDG would eventually publish hundreds of IT magazines around the world, including Computer World and PC World.

Author Glenn Rifkin worked for McGovern as an editor at Computer World during the 1980s and has a new book out called "Future Forward," examining the legacy of McGovern's work, featured on Morning Edition.

Podcast: Glenn Rifkin author of ‘Future Forward’ book about Patrick McGovern

CBS News Tech Analyst Larry Magid sits down with Glenn Rifkin, author of Future Forward: Leadership Lessons from Patrick McGovern, the Visionary Who Circled the Globe and Built a Technology Media Empire.

Although not as famous as some leaders, McGovern, who died in 2014, was an incredibly important leader in the world of computing and computer publishing. He had an impact on thousands of people, including myself and his biographer Glenn Rifkin who chronicled McGovern’s professional life not just as a way to memorialize a man but to understand the principles behind his success and his impact on those who he influenced.

This 35 minute interview is worth a listen not just for those who want to learn more about McGovern, but anyone who wants to learn about what it takes to be a leader.

''Future Forward'' Examines A Tech Titan You May Never Have Heard Of

International Data Group, IDG, is known as one of the most influential media empires in the world, but was started out of MIT graduate Patrick McGovern's house in Newton in 1964.

International Data Group, IDG, is known as one of the most influential media empires in the world, but was started out of MIT graduate Patrick McGovern's house in Newton in 1964. Author Glenn Rifkin, who worked for McGovern as an editor at Computer World in the 1980s, examines his late boss's legacy in his new book, "Future Forward."

Interview Highlights

On who Patrick McGovern was

"He was the entrepreneur and visionary who started a company called International Data Group, IDG. And what he saw was that the information technology revolution was getting started in the early '60s, it was slow and steady. But he saw something bigger happening, and over those years he decided that somebody needed to tell the story of this revolution. It was one thing to be the Bill Gates or the Thomas Watson Jr., who made things — the software and the hardware. But somebody needed to chronicle what was going on, and that was his mission.

"He created actually nearly 300 publications around the world over the course of 50 years running the company. The first publication was Computerworld, which became the Bible of the information technology industry. ... It was news, weekly news, it was product reviews and things like that, but mostly it was taking a look at the people and players in the industry, the companies that were moving and shaking. They were big in covering IBM in the late '60s into the '70s when they were the 800-pound gorilla in the industry space, and as it moved along, as the industry changed — the personal computer was created in the 1980s — Computerworld be the newspaper of record, so to speak. It was kind of the New York Times of the computer industry."

On working for McGovern at Computerworld

"I joined in 1983. At the time, [I] didn't know a computer from a washing machine. If I could turn on the on switch, I was happy. Never dreamed of getting involved in the technology industry. But I got a job there at a time when jobs were a little bit scarce, and ended up just loving it, because something really exciting was happening. I started interviewing Bill Gates and Steve Jobs before The New York Times and Wall Street Journal did. So I was right there, as I say in the book, at the tip of my keyboard, things were happening. And I stayed there for seven years, during which time I got to know Pat McGovern."

"It was one thing to be the Bill Gates or the Thomas Watson Jr., who made things — the software and the hardware. But somebody needed to chronicle what was going on, and that was his mission." Glenn Rifkin

On how McGovern interacted with his employees

"There's lots of visionaries, lots of entrepreneurs out there who've done great things. But Pat had a very unique style of management and leadership, which is what the book is about. He saw the world differently. He didn't need to be in the spotlight. What he wanted was to fulfill a mission, and one of the keys to him to fulfill this mission was to treat his employees around the world in a way that most companies didn't.

"This was a guy, for example, at the holidays, he would go around to every office in the United States — we're talking about 5,000 people at the time — he would go to every desk, he would meet and greet every employee. He knew if you had worked there before and he'd seen you the year before, he not only remembered your name, he knew your wife's name, he knew how many kids you had. He would congratulate you on some project that you did, and he would thank you for the contributions you were making to the company. And then he would hand you a holiday card, which was stuffed with cash, a holiday bonus, and people were blown away by this. ... This need, this desire to make a connection to every employee, I mean I can't think of another CEO who did that."

On McGovern's willingness to give people a long time to try things out and experiment

"One of Pat's mottoes, one of the actual corporate values, the 10 corporate values of the company, is, 'Let's try it.' His idea was that great ideas were going to emanate from everywhere and anywhere inside the company. If somebody was smart enough to come up with the idea, could make a case for the idea, he said, 'Let's try it.' And he would give you some funding and he would let you go with it. It created numerous publications, it created numerous opportunities.

"One of the great stories that came from that attitude was the 'For Dummies' books, those are from him. ... They started a book division, and they had this gentleman named John Kilcullen who'd come in, the division wasn't doing well at all, he remembered a story about a friend who was at a computer store back in the '80s and asked the clerk, 'Listen I need a book about this MS-DOS thing. But I don't know anything. It's got to be something like "DOS for Dummies." ' And Kilcullen remembered that title, suggested to McGovern, 'Let's do a series of books about this,' and McGovern thought, 'Well, we're insulting our readers if we're calling them dummies.' And Kilcullen said, 'No. What we're doing is' — this is pre-YouTube, pre-internet — 'we can give them really reasonable instructions on how to be smart about technology, because technology is complicated.' So they went with that, and the 'For Dummies' books became this remarkable global brand. I mean, literally two or three thousand titles in print."

Book Excerpt: 'Future Forward' by Glenn Rifkin

By Christmas of 1983, I had been working at Computerworld for nearly a full year. For a technology neophyte, this immersion into the exploding computer industry was astonishing. A revolution was underway as personal computers, networks, and powerful new software applications were fueling a shift in both the business and personal sides of this world. Computers were moving from glass enclosed data centers to individual desktops, and the implications were enormous. Being at Computerworld, widely considered the bible of the technology information marketplace, was a fortuitous happenstance, a front-row perch from which to observe and meet the likes of Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Larry Ellison, Thomas Watson Jr., Ken Olsen, Mitchell Kapor, and other industry heavyweights intent on changing the world.

This was before the advent of Apple’s Macintosh, Microsoft’s Windows, the Internet, smartphones, Wi-Fi, broadband, and the flood of technology-driven upheaval around the globe. But you could feel the earth moving, and there wasn’t any doubt that something big was happening right at the tip of your keyboard. For journalists like me, whose careers were birthed when electric typewriters and Wite-Out were de facto tools of the trade, this new era was exhilarating.

Inside Computerworld, on a wintry afternoon a couple of weeks before the holidays, a buzz of a different kind was sweeping through the weekly newspaper’s editorial offices in Framingham, Massachusetts. Word got out early in the day that Patrick J. McGovern, the formidable founder and CEO of our parent company, International Data Group (IDG), was going to be making his annual holiday rounds. Although the several hundred staff members in the building were adults, the feeling could only bedescribed as giddy, a childlike sense of anticipation that reminded me of grade-school birthday parties.

I had seen McGovern in the building a few times during the year, but we had yet to meet, and he had already taken on the Paul Bunyanesque persona that turns ordinary businesspeople into celebrities. Larger than life, he was a big man who stood six feet, three inches tall and had the burly build of an NFL linebacker. He had a loud, distinctive voice and laugh that could be heard across a huge room. When we got word that Pat was in the building, work essentially ceased. We stayed at our desks in the cubicles that dotted the newsroom, feigned effort, but accomplished little as Santa in a dark blue suit and yellow tie approached.

To be clear, our excitement was not only due to the wide-eyed exuberance of celebrity worship. There was the mercenary, Pavlovian vibe that emerged with the reality that Uncle Pat, as he was fondly called, had arrived with a Brinks truck loaded with some serious dough for each of us. He was here to hand out Christmas bonuses, and though the amount was meager compared to the six-figure bonanza bonuses of Wall Street investment bankers, it was a considerable sum for blue-collar journalists, production workers, and sales staff. That year, the bonus was equal to a month’s pay, and that was a good reason to anticipate his arrival.

What made the event more memorable was the fact that McGovern, a media mogul by any measure, a wealthy, self-made visionary who transformed the technology information and research industry, handed out every envelope personally. He stopped at every desk, greeted every individual by name, shook hands, chatted about their work, their families, their dreams, and left behind a glow of good feeling that dwarfed the money and created an indelible imprint.

The fact that he did this with every employee in the company in every office in the United States was mind-boggling. By the time I joined, there were 13,000 employees around the globe and 5,000 in the United States alone. The scope of his effort, his determination to make that personal connection, spoke volumes about the man.

For those of us who had worked at other companies, the idea of the CEO personally delivering a bonus and a good word was pure fantasy. If you were lucky, you got a cooked turkey, a Swiss Army knife, or a holiday memo from the chief to the troops. The odds that the CEO would personally deliver said turkey were very slim. But Pat McGovern was a different kind of executive, an iconoclast who was driven not merely by profit but by a desire to better the lives and careers of his employees and a lifelong calling to understand technology’s impact on humanity. He was indeed on a mission.

When Pat McGovern started the company in 1964, not long out of MIT, he had a perfect combination for entrepreneurial success: an abundance of self-confidence, a prescient vision, and a wellspring of curiosity to find out what he didn’t know and spread this information around the globe. In an era when computers were giant, mysterious, unattainable machines guarded by the high priests of the data center, McGovern foresaw an immense shift in the power of these machines to impact individuals, to enhance the human brain, and to spawn a better future. That he operated in a familial manner and built an employee friendly corporate culture just added to his reputation. In the 1980s, the era in which Gordon Gekko declared, “Greed is good,” Pat McGovern chose to share the wealth. That’s not to say he wasn’t making a fortune for himself, because he was. He became a billionaire and was a regular on the Forbes list of the richest people. What he proved was that being good to his employees turned out to be a very sound business strategy.

If you were lucky enough to be part of the workforce near where IDG was headquartered in Massachusetts, the Christmas bonus was only the beginning. The company threw a lavish annual holiday party, hosted by McGovern and his wife, Lore Harp McGovern, in a ritzy downtown Boston hotel just before Christmas. Attendees brought their spouses and significant others, ate and drank and danced the night away, and some went home with door prizes of trips for two to tropical resorts, ski chalets, and Europe. Each year, McGovern and the executive team would create a holiday video to share the habitually positive corporate results and thank everyone for a job well done. Dressed as Star Trek’s Captain Kirk, Batman, Ben Franklin, Obi-Wan Kenobi, or James Bond, McGovern showed no reluctance to shed a little dignity for a good laugh.

News staffers went on an annual trip to resorts in the Bahamas or Puerto Rico for an “editorial meeting,” and IDG was among the first companies in the country to take advantage of federal regulations allowing employee stock ownership programs. The ESOP created a cadre of millionaires among IDG’s longest-serving employees and allowed others, such as me, to take a nice nest egg along with us when we left the company. Many who departed for jobs at rival organizations realized quickly that they’d made a mistake and returned to IDG.

What McGovern created was a large extended family. In a high powered,often cutthroat industry like high tech, it was unusual to feel part of a culture of inclusion where your CEO had your back, valued your ideas, prodded everyone to push their own envelopes, and accepted failure as a stepping-stone to achievement.

As my tenure continued, I came to learn that McGovern’s contributions far exceeded the corporate largesse. The empire he had built starting in 1964 played a major role in the evolution of computer technology around the globe. The emergence of information technology as a mainstream business topic was happening as I immersed myself in the stories of automation, desktop computing, software, networks, and a shifting computer landscape that was changing the world. I found myself covering the same people and companies as the Wall Street Journal, Businessweek, Fortune, and the New York Times. Indeed, we were out ahead of all those publications because Computerworld had staked this territory nearly two decades earlier.

The tiny 1960s startup that became a global tech-media empire

IDG brought us PC World, Macworld, and other familiar brands. But first, it produced a newsletter from a house in suburban Boston.

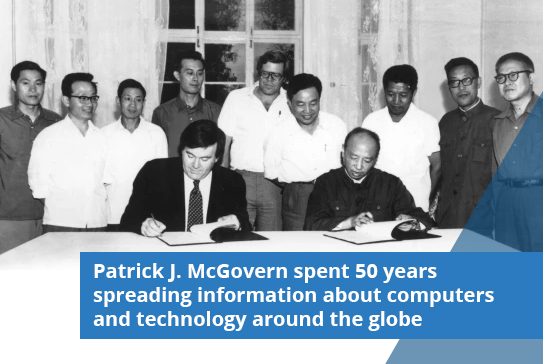

Patrick J. McGovern (1937-2014) spent 50 years spreading information about computers and technology around the globe through publications such as PC World, Macworld, Infoworld, the Dummies books, and the company’s flagship, Computerworld. In 1964, when the company was new, the computer industry was still emerging, and McGovern’s first project was to collect some basic data about it. Glenn Rifkin’s new book, Future Forward: Leadership Lessons from Patrick McGovern, the Visionary Who Circled the Globe and Built a Technology Media Empire, chronicles McGovern’s decentralized, entrepreneurial, and highly successful approach to business. This excerpt covers the company’s earliest days and first forays into publishing.

Of all the leadership lessons he took to heart during his long career, Patrick McGovern intuitively grasped one of the most important early in his career. In order to build a successful enterprise, you have to identify a clear mission from the outset and find effective ways to share that mission with your people. Before Google and Facebook turned hiring into a science and carefully screened every new hire, McGovern pulled together an eclectic and enthusiastic group of young employees for his fledgling company in a less analytical but highly effective manner. He shared the goals and strategies, but he imparted the mission—to propagate the benefits, understanding, and acceptance of information technology around the world—through sheer determination and passion for what he was doing.

New employees got swept up by this large man with an outsized dream. For example, when he was 23 years old, Burgess Needle lived in the gray house at 355 Walnut Street in Newtonville, Massachusetts. A student at a junior college across the street, Needle rented an upstairs room from McGovern, who owned the house and had reserved the first floor for his startup, International Data Corporation (IDC). It was 1964, and McGovern was just a few years older than Needle but had the ambition of a seasoned business veteran.

On that first floor, McGovern had created his first industry report, which was essentially a census of all the mainframe computers installed in the United States. With IDC up and running, McGovern accelerated his already ambitious efforts. IDC would become celebrated for its role in counting all the world’s computers, a staple of its practice to this day. But for McGovern, this was just a beginning. He foresaw a burgeoning audience for market share data and forecasts. In order to create a steady revenue stream, he created the Gray Sheet, which found a big audience among computer makers and their corporate customers who were seeking vital information about the nascent technology landscape.

The Gray Sheet was the first publication of what would become a global publishing empire, but its humble beginnings offered a glimpse of McGovern’s tenacity in creating the mission that would drive him for the next 50 years. He wrote the newsletter himself from data gathered by a tiny staff of young part-time stringers, and his new assistant, Susan Sykes (who would soon become his wife), typed up his notes. The youthful staffers were on the phone calling the giant computer vendors and their customers to gather as much information as they could about computer installations.

In the first issue, dated March 23, 1964, McGovern laid out an impressively detailed look at the computer industry landscape, a marketplace dominated by IBM but with an array of hungry and aggressive competitors. “From all indications,” McGovern wrote, “1964 will certainly be a turning point year in the development of the American computer industry.” Indeed, as more and more corporate, government, military, and academic institutions began installing these massive computers, the information technology industry was in the midst of explosive growth. McGovern knew he was tapping into something potent and lucrative—a game-changing shift in both business and society.

The lead story trumpeted a yet-unnamed new IBM computer system, predicted to debut in April. The headline noted that IBM “Expects to Install 5000 of Its New Computer Systems in Next Five Years.” McGovern, who’d been editor of both his high school and college newspapers, boldly predicted sales of more than $3.5 billion for Big Blue over that period, a stunning figure for any manufacturer in those days. The new computer turned out to be the IBM System/360, the first “family” of small to large computers, which would transform the industry.

That first issue also promised a monthly assessment of sales from all of the computer makers, including major competitors such as Honeywell, Univac, Control Data, Burroughs, and RCA, along with critical analysis of each company’s sales efforts. Given the dearth of such vital information, he found a ready audience more than willing to pay.

“What struck me was his work ethic,” Needle, now a Vermont-based poet and librarian, recalled about McGovern. “He would be there day after day, morning till night, 16 to 18 hours, putting together the newsletter. I’d be upstairs, but one time I walked downstairs at 3 in the morning and there was Pat ready to go out for a run. He was wearing a T- shirt, running shorts, and running shoes. He said, ‘I’m too revved up. I have to work this off,’ and he went up to the track at the local high school and ran a few laps to clear his head. He came back, showered, and went right back to work. His energy was unreal.”

Needle, a liberal arts major and budding writer, had worked at a local deli, but one day the deli burned down, and he was out of a job. McGovern said, “Come work for me.” Needle responded, “I don’t know what I can do for you.” Computers and math were anathema to him. But McGovern suggested he take a generic aptitude test to see if he was qualified. Reluctantly, Needle agreed. The test got progressively more difficult as it went along, treading into logic, semantics, and other esoteric fields.

“There were 33 questions,” Needle said. “By the time I reached 28, I just stopped and said, ‘This is as far as I can go.’ Pat glanced at it and said, ‘You’re hired.'” McGovern explained that anyone who scored over 27 would be bored out of their mind by the work. Under 17 and they wouldn’t be up for it. “You had 23 correct,” he said to Needle, “so you are perfect.”

Needle joined the young company as a part-time employee. He cold-called companies up and down the Eastern Seaboard and, using a questionnaire McGovern had written, asked the data processing managers what kind of equipment they had, what they were doing with the equipment, and what their needs were. Needle wondered why these giant computer vendors would buy data from this tiny unknown startup operating in a tranquil Boston suburb. Didn’t they have their own resources to get the information? And why would data processing executives talk to him about proprietary corporate information such as their inventory of computer equipment? McGovern told him, “They’ll talk because they are proud. They’ll be delighted to share this information. These are people who don’t have the opportunity to share with anybody. You’ll have to shut them up.” And he was correct.

McGovern, reacting to his recent conversation with the CEO of Univac, only saw opportunity. “We need this information,” the Univac chief had told him, and McGovern saw quickly that he was right. His research might seem like small change to these giants, but it could spawn bountiful leads for their sales forces. It was audacious, and it worked.

His readers, who were eventually willing to pay upward of $500 a year for a subscription, were on board because the information was scarce, timely, and valuable. “I would see him on the phone with people trying to track down a rumor about a new high-speed printer or some other computer peripheral, and you could tell the person was not very forthcoming,” Needle said. “Pat would talk, tell a joke, circle back, and finally he’d smile, tap the desk, and I would think, ‘Got it.'”

A POTENT OPPORTUNITY

At age 27, McGovern displayed the kind of doggedness and risk-taking spirit that would characterize a later generation of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs. From the first days, he understood his mission, and the company coalesced around that mission. Burgess Needle stayed with the startup for less than a year, choosing instead to pursue a literary career. But tens of thousands of others, from California to Beijing, would eventually join IDG and embrace McGovern’s mission. The people he hired learned fast, bought in, and became expert in their various industry niches. He had an almost mythical persona that attracted these young, talented writers, editors, artists, and salespeople who propelled the company to the top of the flourishing information technology media industry.

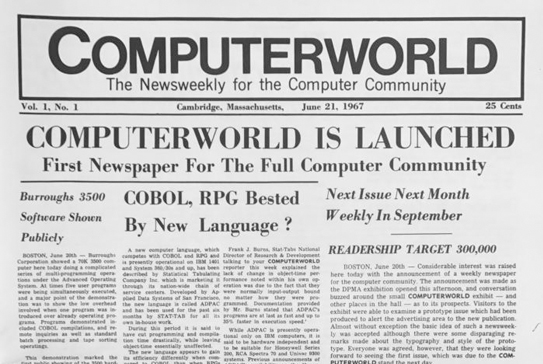

Just three years after he founded the company, in June 1967, McGovern published the first issue of Computerworld, a weekly newspaper that chronicled the news and events shaping the now mushrooming computer industry. In so doing, he took IDC into the emerging technology publishing arena, established a brand that would quickly become a dominant force in the industry, and began a period of sustained and phenomenal growth.

A scientist by nature, McGovern believed in the data. He was among the first in the computer industry to understand the value of surveying professionals in the information technology field. Computerworld emerged, not on a whim, but from listening to these early computer users voice their concerns. McGovern recalled an early research project IDC was conducting for a client to identify the sources of information for people who bought computer systems.

“We went down and interviewed about 40 people who were data center heads or computer center heads,” he said. “They were all telling us the same story. They said, ‘I get a tremendous amount of literature from the manufacturers.'” These computer makers and their marketing and advertising campaigns, replete with the biases of companies pushing their own products and agendas, seemed to be the sole source of information for prospective buyers.

“What I don’t get,'” said one data processing manager, “is visibility as to what my colleagues are doing. Because I know that they’re having the same concerns about acquiring and using this equipment effectively and well, and problems with some of the reliability of the equipment, and how to train their people. It is a shared challenge for us.”

The trigger for McGovern came next. “There isn’t anyone who keeps us connected as a community, who keeps us up to date and aware,” the manager added. “There are so many things happening, we’d really like to get high frequency information.” Hearing that, McGovern saw through the frustration and angst to a potent opportunity. A weekly newspaper, staffed with talented journalists and editors, could find a ready audience, an audience willing to pay a subscription fee to get the timely and discerning information they needed. In creating Computerworld, McGovern set a new template for his mission.

He changed the company’s name to International Data Group, split IDC into a separate research arm, and soon after, decided to legitimize the “International” in the company name by taking his vision overseas. The mission crystallized. IDG would provide information services about information technology, and though the elasticity of the objective allowed for occasional twists and turns, the ultimate success was built upon a steadfast devotion, over the next half-century, to the core mission. It was a lesson from which McGovern would rarely deviate.

Patrick J. McGovern and the birth of Computerworld

More than fifty years ago, in June 1967, Patrick J. McGovern, a young entrepreneur with a vision about how technology could change the world, published the first issue of Computerworld. The IT newspaper quickly grew into a global business that continues to cover the tech industry even today.

From the start, Pat McGovern intended for it to be an IT publication that delivered good quality journalism and computer industry news faster than the competition.

Like many start-ups that were born in garages, Hewlett-Packard or Apple, Computerworld was being run by MIT graduate Pat McGovern, out of his colonial style home. He was 30 at that time, and had started the IT publication just 3 years after founding International Data Corporation (IDC). IDC did research on emerging markets, where Patrick, who had a degree in biophysics and a passion for traveling, had seen enormous potential in what technology could offer.

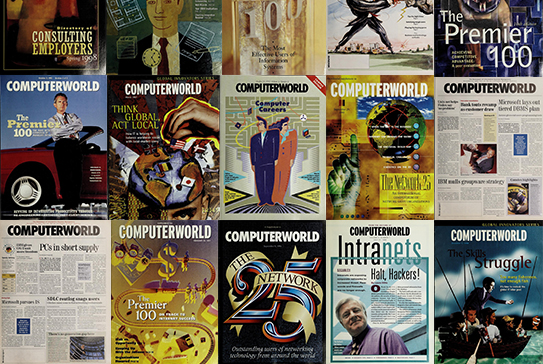

The visionary idea of Computerworld, a newsweekly for the IT community, came in the 60’s while he was at an industry trade show. He envisioned something that would help users understand how technology could help their businesses grow. From those early days, Computerworld and IDC would grow over the years into International Data Group (IDG), including 300 publications in 97 countries, like NetworkWorld, InfoWorld, PCWorld, CIO and CSO, as well as IDG News Service, over 450 websites and 700 events.

Computerworld's 50 years of publishing

2017 was an important year, marking the 50th anniversary of Computerworld’s founding. The first full editorial issue of Computerworld was launched June 21, 1967.

Back in 1967, Thursday mornings were special, when the first issues of Computerworld were usually delivered from printers. The computer industry was flourishing in 1967: IBM created the first floppy disk, the first Computer Electronics Show (CES) debuted in New York City, and Chase became the first video game that could be played on a TV.

In 1973, McGovern launched Shukan Computer (the first international version of Computerworld) in Japan. While it was a Computerworld for that country, Pat didn't try to duplicate the content from his U.S. publication. He wanted each overseas IT newspaper to be unique, with a local staff that could tailor the content to the concerns in their home markets.

In 1980, McGovern established one of the first joint ventures between a U.S. company and one in the People's Republic of China, and in 1992, McGovern established IDG Technology Ventures, one of the first venture capital firms in China. In recognition of his great contribution to China's information industry and venture capital field, he was awarded the “International Investment Achievement Award” at the CCTV 2007 China Economic Leadership Award ceremony in Beijing. This was the first time the award was given to a foreign investor.

Over 50 years, Patrick McGovern built a large empire consisting of three primary groups: IDG communications, the publishing arm (including Computerworld), the IDC research arm, and IDG Ventures, an investment firm that focuses on up-and-coming technology businesses. And that is just in the U.S., IDG operates in 97 countries around the globe.